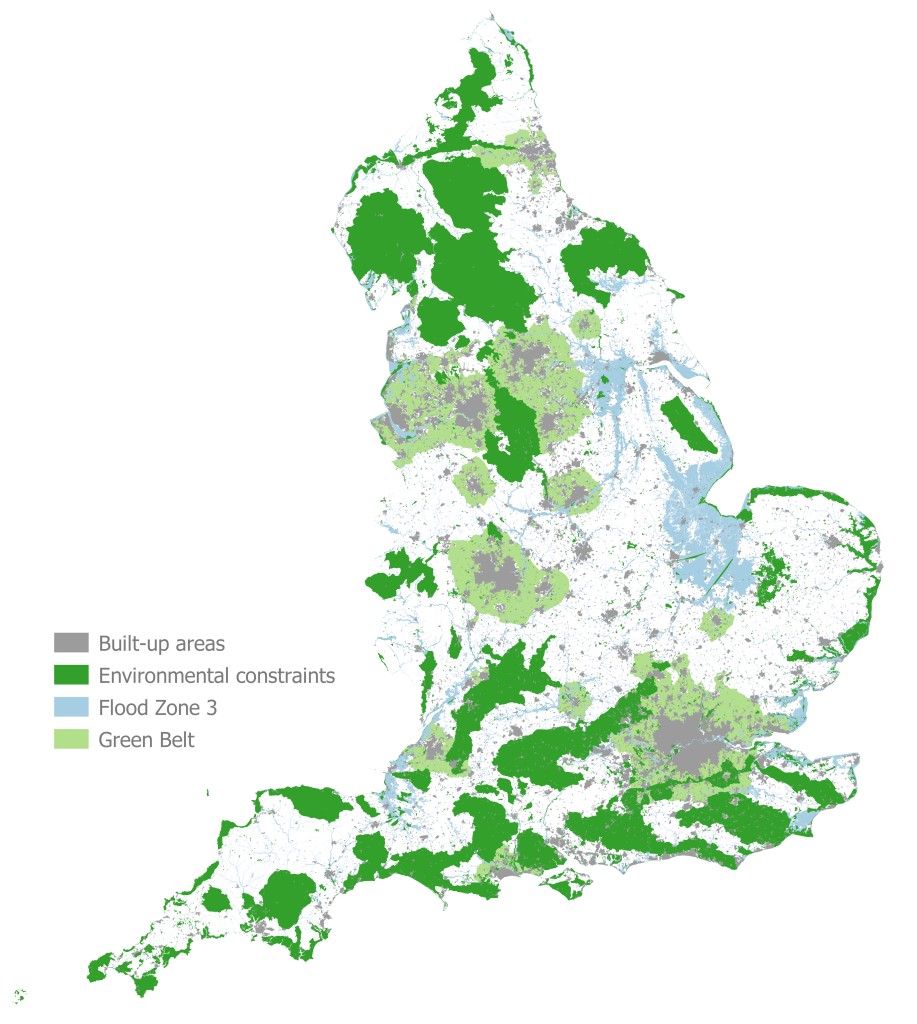

Labour’s new emphasis on housebuilding seems to break a Green Belt taboo that has gripped all the main parties for decades. Has the electoral calculus finally changed? I’ve taken a look at the numbers.

The truth is the housing crisis won’t be solved without allowing cities to expand into some parts of the Green Belt, but politicians have consistently calculated that doing so is a vote loser. But as Jonn Elledge has pointed out, Labour may now be at a point where it’s not such a gamble if the constituencies affected are mostly never going to vote for them anyway. So does the data back this up?

England accounts for 533 of Parliament’s 650 constituencies*. Of these a surprisingly high 316 (59%) have some Green Belt, albeit sometimes only a sliver. And of the constituencies with Green Belt, 194 are held by Conservative MPs (well, they were in 2019 anyway…), that’s 61%.

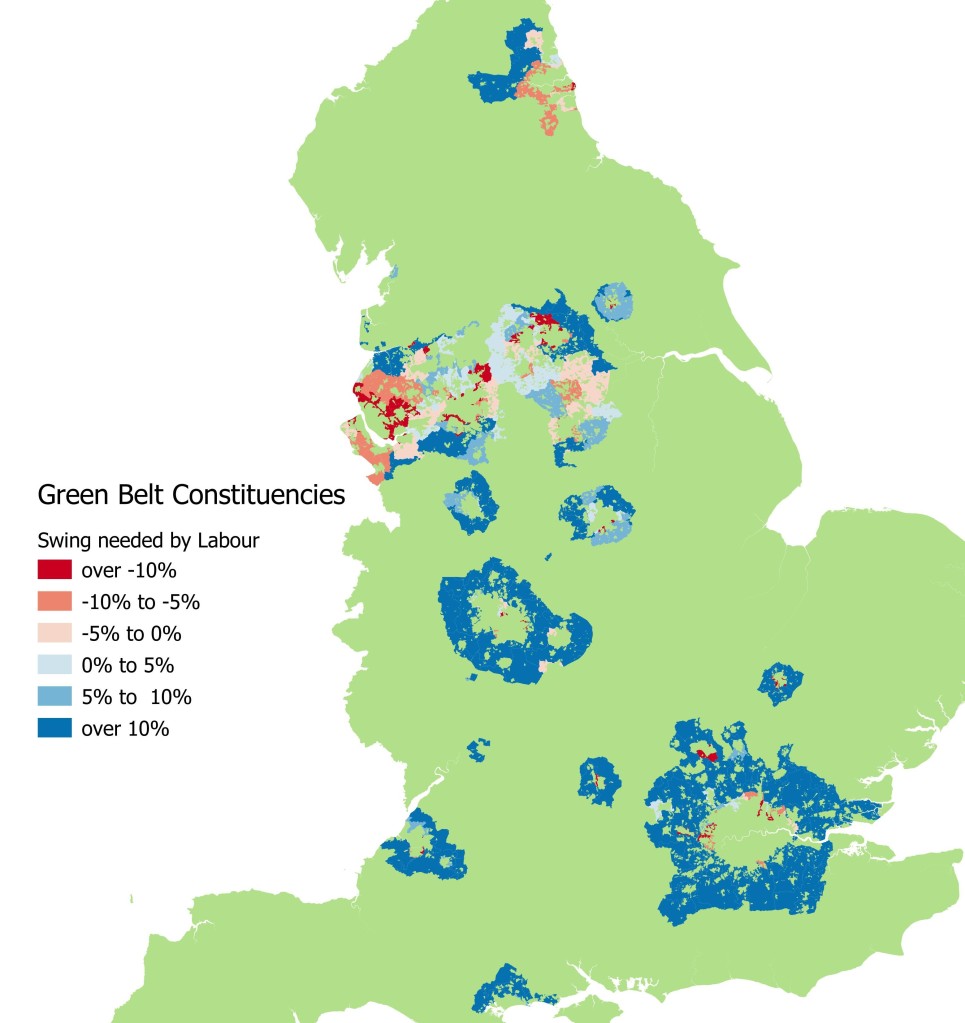

But here’s where it gets interesting for Labour. Of those 194 English Green Belt Tory seats, 140 would need a swing of over 10% for Labour to win. Not impossible, but safe seats that are perhaps mostly not necessary for an overall majority, so are not target seats**.

And on the other side, a further 29 seats would need a swing to Labour of less that 5%, perhaps close enough that Labour could still overcome a nimby backlash – current polls equate to a swing of about 15%.

So there are just 25 seats where there is Green Belt and Labour need a swing of between 5-10% – electoral territory where anti development sentiments might sway things. In two of these, Labour are not the second placed party, so may not be challenging anyway. And one has less than 1% Green Belt, so may not be a significant issue.

That leaves 22 seats (just 3% of the total seats in Parliament) where Green Belt housebuilding might be a local issue for Labour. Interestingly, only five*** are in southern England where housing pressure on the Green Belt has arguably been most politically charged. A further six are in the Midlands, and 11 in the North.

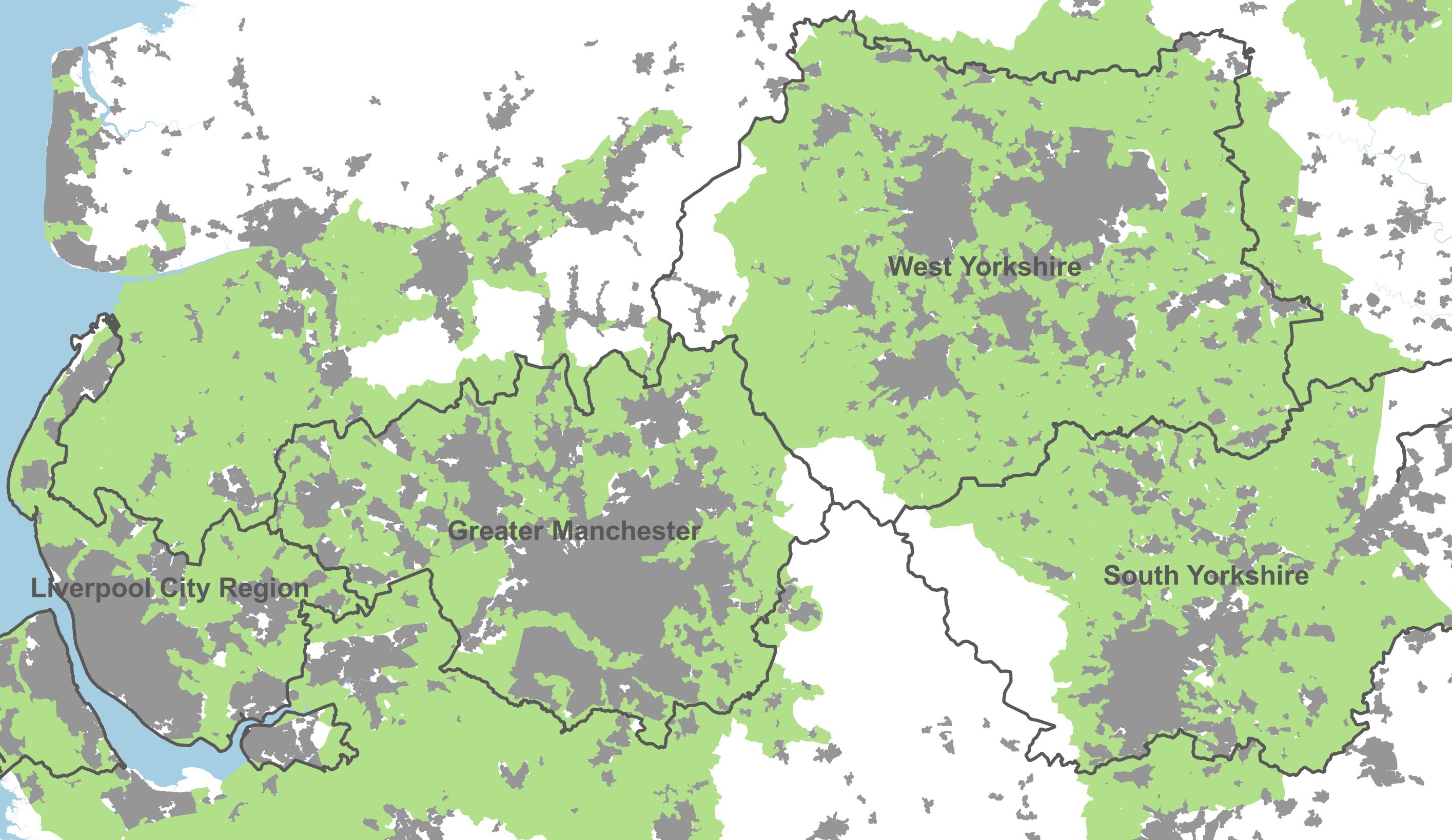

To see what that looks like, the map below shows constituencies in the English greenbelt coloured by the swing needed by Labour take them. Dark blue are safe Tory seats, most of which Labour wouldn’t need to form a majority at the next election.

Perhaps finally we really are at a point where there could be an electoral majority for housebuilding.

* Note I’m using 2019 boundaries, for simplicity, and using the 2019 general election results

** I’m no psephologist, and am simplifying greatly here. Draw the lines differently and the numbers will change.

*** Harrow East, Uxbridge & South Ruislip, Stevenage, Bournemouth East, and Filton & Bradley Stoke